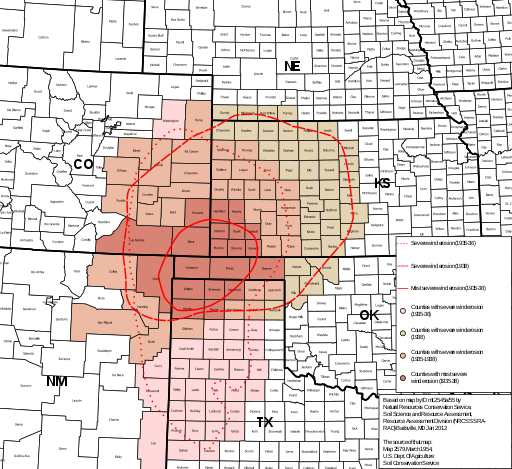

Soil Science and Resource Assessment, Resource Assessment Division (NRCS SSRA-RAD) (Division of the U.S. Dept. Of Agriculture), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In my most recent blog post, I discussed a few of the factors behind the cause of the Dust Bowl, and ways human folly combined with natural cycles to create one of the worst man-made natural disasters in our recent history. In this post, we will discuss the scientific technicalities of those cycles, and examine how we can work with the earth responsibly and (hopefully) prevent future Dust Bowls from ever coming to fruition.

Looking Back through a Scientific Lens

Contemporary scientific studies that aim to examine the Dust Bowl look to surface sea temperatures (SSTs), General Circulation Models (GCMs), and soil degradation as the three main causes of the Dust Bowl. Two of these (SSTs and GCMs) are analyzed by looking at earth cycles combined with man-made impacts. The final (soil degradation) is known to have originated from new landowners who were called by governmental authorities to plow up all the buffalo grass in the Great Plains. This resulted in a complete depletion of nutrients from the soil that would sustain farm life.

Today, SSTs are employed to understand how the earth’s atmosphere and oceans interact. They are also used to determine the annual weather cycle we are in – whether we are in an ‘El Niño’ and ‘La Niña’ year. In the Dust Bowl, SSTs were unusually elevated, and combined with the man-made desert microclimate in the US Central Plains. This created a negative feedback loop, which had a much larger impact. Effects of the Dust Bowl were experienced as far away as New York, as huge dust clouds rolled around skyscrapers and clouded visibility on May 11th, 1934.

Recently, scientists have also looked to Global Circulation Models (GCMs) to see how macroclimates interact with microclimates. GCMs are determined by using the following criteria:

- The atmospheric component, which simulates clouds and aerosols, and plays a large role in transport of heat and water around the globe.

- The land surface component, which simulates surface characteristics such as vegetation, snow cover, soil water, rivers, and carbon storing.

- The ocean component, which simulates current movement and mixing, and biogeochemistry, since the ocean is the dominant reservoir of heat and carbon in the climate system.

- The sea ice component, which modulates solar radiation absorption and air-sea heat and water exchanges.

By examining these factors today, and simulating previous global circulations, scientists can determine what environmental factors combined and became the cause of the Dust Bowl.

What did Buffalo Grass actually do?

John Tann from Sydney, Australia, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Farming by machined tilling has proven time and time again to be detrimental to the land and the people inhabiting it. In the events leading up to the Dust Bowl, topsoil and native prairie grass were removed, and nothing but dust and drought existed in parts of the Central Plains. So, how did the native grasses on the Great Plains actually support a health microclimate?

In general, native grasses provide soil with biomolecular organisms that help the earth retain biomass. Biomass is the carbon content of stored energy in plants. In interactions with the atmosphere, higher carbon content in the earth offsets the amount of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide is not bad on its own, but excesses are not desirable and cause catastrophes like the one we are currently facing – global warming. Without carbon content in the soil, there is no carbon content in crops, which leads to little to no nutrition in the food grown. Minimal vitamins and nutrients can be consumed from crops of this kind. After a season or two of machined tilling a large percentage of that high biomass topsoil is lost. Without topsoil, we get desertification, which further exacerbates the problem of no biomass, and gives us dust – tons of dust. Without diverse prairie grasses, the negative feedback loop of man-made disaster drones on.

What can we do?

One way we can prevent massive amounts of desertification is to minimize the amount of tilling we do in our gardens and on our farms. The microbiome present in soils where the ecosystem is healthy is heavily disturbed when tilling is the prime method of soil prep for a growing season. There are numerous well-established methods that do not involve tilling at all or are minimal in prescriptions for tilling. There is sheet-mulching, Hugelkultur, and other hybrid methods that will not tamp the health of your soil. Low to no till practices will also prevent desertification of the microclimate you are establishing when you plant.

The official solution to the topsoil problem occurring in the Dust Bowl was to plant large swaths of wheatgrass that could survive in a desertified climate. However, in this solution one of the most important aspects of any thriving ecosystem was ignored – biodiversity. The truth about monoculture (or one large geographical area of a single species of plant growth) is that it will not provide adequate ecosystem support to wildlife. For instance, certain species of bird might be dependent upon one species of insect for survival, and that insect might need more than one species of grass to survive. There is a whole system at play here. Therefore, maintaining biodiversity in an ecosystem is ever important.

Think about the accepted systemic methods of growing fruits and vegetables. When we plant our food crops, we focus on providing each plant a wide variety of supportive plant species. We need flowering plants to give bees, beetles, flies, bats, and other pollinators what they need to do their job and survive. Pollination of those flowers results in fruits and vegetables, as well as more flowers. The best possible way to maintain biodiversity is to focus on planting natives. Natives support the established microbiome and the flora and fauna of the ecosystem.

Conclusion

I’ll give you the good news first: we are on the other side of this tragedy that devastated families, livestock, and most of all the earth. The bad news is that we are not out of the weeds. In a recent article, NPR reported the Midwest is now devoid of top soil. This is directly related to tilling, and more specifically machined tilling of the topsoil to produce crops. Tilled crops like the ones that have wiped out topsoil in the US Midwest require intensive applications of toxic pesticides to produce adequate amounts to support farmers living on government subsidized lands and growing government subsidized seed. Pesticides leach into the soil and eliminate not only the microbes that bolster entire ecosystems, but also into the food produced. No microbes in farmed food means no microbes in our gut. And that means most of our bodies (made of bacteria – microbes) are not receiving the support needed to function properly. Acutely this is no problem. The human body is strong and resilient in the face of immediate and short-lived pressures. It cannot, however, withstand constant onslaught which leads to chronic ailments.

It is obvious that we as growers have a duty to the soil. Making sure we are not a part of the huge problems we currently face is also imperative. Permacultural solutions and a native focus allow us to do what we need to do and support the biome of our locality. It is worth looking into and observing the ecology of your locality too. And most of all, do not lament so much about the state of the earth that you cannot see the forest for the trees. We need you, and we need your help!

The featured image for this post was sourced from Arthur Rothstein, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Recent Comments